For water, geometry matters: the importance of spaces shape in cells

|Inside living cells – environments crowded with organelles and macromolecules – water moves, bonds, and reacts in a particular way. But is it possible that the shape of the space that water occupies in cells can control how water itself behaves?

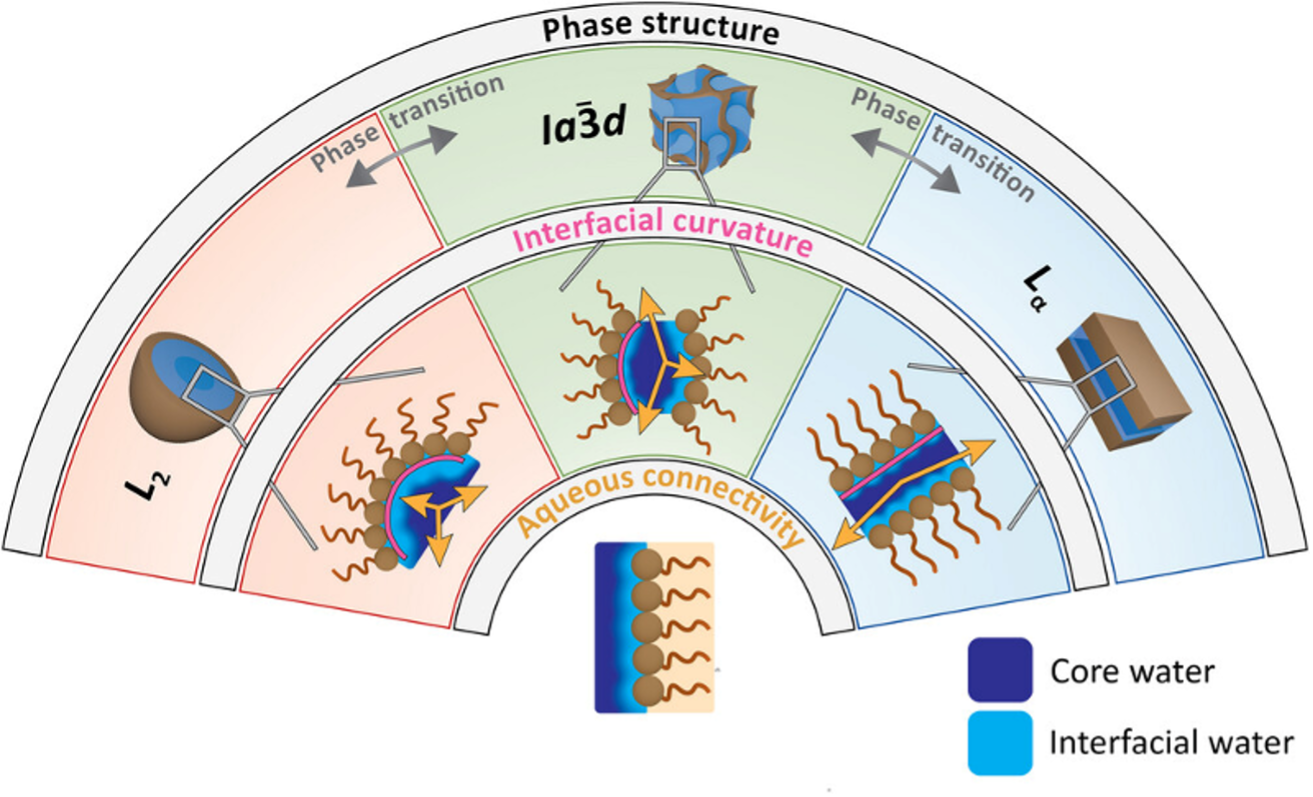

To investigate this, Sara Catalini (University of Florence), Yang Yao (University of Basel) and colleagues exploited model systems made from special lipids inspired by archaea, microorganisms that thrive in extreme environments like hot springs. These lipids can self-assemble with water into well-defined structures, known as lipidic mesophases. By adjusting temperature and hydration, scientists could switch between three distinct arrangements: flat layered membranes (lamellar phase), a complex sponge-like structure with continuous water channels (a cubic “gyroid” phase), and tiny isolated water droplets surrounded by lipids (reverse micelles). Although all these phases contain water, their geometry is radically different, and so is the water’s behavior.

In flat layers, water is squeezed into thin, two-dimensional sheets. Near the membrane surface it forms strong hydrogen bonds that slow its motion. In contrast, in the curved, three-dimensional networks of the cubic phase, water molecules can rearrange more easily and move faster. Using a combination of X-ray scattering, calorimetry and multiple spectroscopic techniques (including the ones obtained at the Inelastic Ultraviolet Scattering Offline laboratory, at the CERIC Italian Partner Facility) the research group showed that in these models water consistently splits into two populations: tightly bound “interfacial” water near lipid surfaces, and more mobile “core” water. Crucially, the balance between these populations, and how fast water molecules reorient, depend on interface curvature and water-network continuity, not just on the confinement size.

By controlling the shape and connectivity of tiny water-filled spaces, it may be possible to tune diffusion, reactivity, and transport. These insights could then guide the design of better drug-delivery systems, biomimetic membranes, and nanoscale materials where water plays an active functional role.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE: